Here is a link to the audio from my podcast if you’d like to listen instead, though I do hope you read the article and check out the pictures!

https://anchor.fm/tan-man-baseball-fan/episodes/My-134-Year-Old-Discovery-e13sbv8

What I stumbled upon feels like the baseball card version of the Da Vinci Code and Indiana Jones all wrapped up into one.

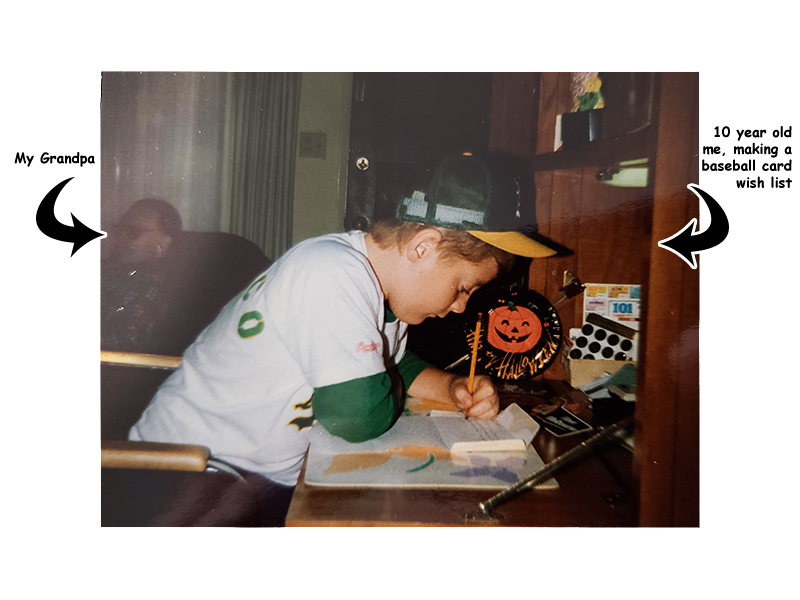

Everyone loves a good treasure hunting mystery, and I guess that’s why I love baseball card collecting so much. As a 9 year old, nothing would excite me more than when mom & dad would bring me home a pack of 1989 Donruss or take me to the baseball card shop. For me, true happiness was finding a baseball card of my hero, Jose Canseco. I would trade with friends in my neighborhood, and discuss the deeper things in life – like who was the best player in the game.

Nowadays, things are different. Footage of Babe Ruth is only a click away on Youtube, the most in depth statistics of any player ever is at your fingertips, and countless videos, images, and collectibles of Mike Trout are all over the Internet. Thanks to social media, we can even keep tabs on our favorite players and see what’s on their mind.

19th century baseball, however, is a treasure trove of untapped greatness that is largely a mystery to even the most knowledgeable of baseball fans. It is chock full of excitement from baseball royalty and pioneers, with endless compelling stories behind each player. Unfortunately for us, we have as much footage of 19th century professional baseball players as we have of dinosaurs. The earliest (and only) known 19th century baseball footage is a 27 second long clip of an amateur game captured by Thomas Edison in 1898.

Without the aid of video and audio, it is easy for people to not care about what happened in the 1800s. Perhaps we tend to think that since the rules were different, that time period doesn’t deserve our attention anyway, so we dismiss what happened back then. But the truth of the matter is that the rules of baseball have been changing all along – even over the past year. What I would contend is that if you truly let yourself become a student of the foundation of the game that was laid back in the 19th century, you will fall in love with it, and be captivated by the countless amazing stories that very few people know. You will also learn that baseball today owes everything to how it was back then.

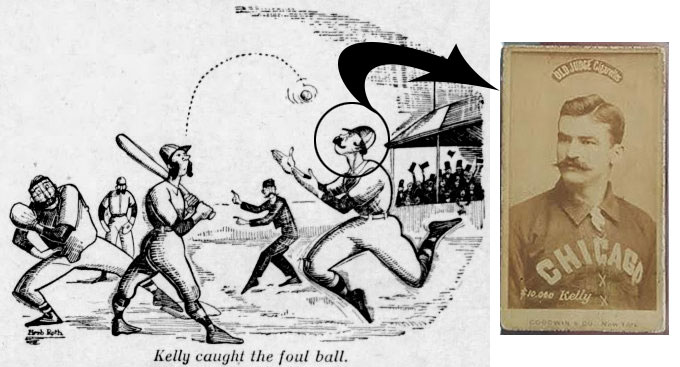

No one on the planet today can say they have witnessed a single pitch from a 19th century professional baseball game. All we have are the stories passed down to us in the form of old newspaper publications, books, and baseball cards. All of these worked together for baseball fans of yesteryear. Stitching together the comics and stories of the papers along with the likenesses found on trading cards would help fans feel closer to the game.

These cards seem to perfectly capture the heart and soul of the time period. They were highly coveted back then as they are today. If it weren’t for the 19th century works of art created to boost cigarette sales, the spirits of baseball past certainly would not shine as brightly as they do now. These miniature masterpieces have preserved 19th century baseball in a way nothing else could, and served as the only way for most baseball fans to catch a glimpse of what their favorite baseball players looked like. The most popularly collected 19th century baseball cards today are Allen & Ginter, Goodwin, and Old Judge. While Allen & Ginter and Goodwin cards are beautiful color lithographs, Old Judge cards are actual photographs.

What makes these cards so incredible is that they are not born of manufactured rarity, but rather are truly rare. They were created to be loved and enjoyed by collectors, and for nearly a century of their lives, there was little regard for their condition – at least in the way condition is scrutinized today.

To give an example of rarity, it has been said that the print run of 1991 Topps is between 2 and 5 million per card. That means the number of 1991 Topps cards printed – just for the regular set would be somewhere between 1.5 Billion and nearly 4 Billion cards total. I remember one time my two car garage was filled with one million cards. If there are 4 billion 1991 Topps baseball cards in existence, that means that there is enough to fill the garages of 4,000 homes – with nothing but 1991 Topps!

By comparison, you could probably fit every Old Judge card in existence in a few boxes. Here is an example of Old Judge rarity: Of the over 1,800 different subjects that PSA has graded, not a single one comes close to how many T206 Honus Wagners have been graded.

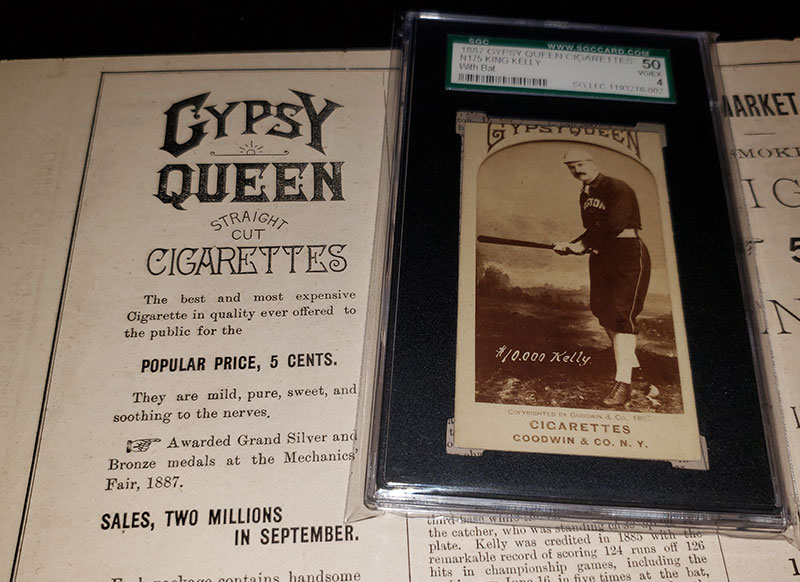

Want to get rarer? Try Gypsy Queen. With an estimated 350 or so total in existence, these little masterpieces typically use the same photographs as Old Judge, but utilize a different border. Though they are extremely scarce, Topps decided to resurrect the brand about a decade ago, which remains a collector favorite to this day.

As a baseball card lover, Old Judge and Gypsy Queen cards intrigue me tremendously. Holding one is truly a special feeling, as you can’t help but stare at one, and wonder where it was during the world wars, how it survived for over 130 years, and who held it previously. What did the first owner feel when they pulled it from the cigarette pack? Did they study it intently to get a feel for what their favorite player looked like for the very first time?

Portrait of a King

All these questions and more intrigued me enough to go on a mission to acquire some of these gems for my collection. After buying and selling a handful of them, I found out what intrigued me most, and that was none other than baseball’s first superstar, Michael Joseph Kelly. You may know him better as King Kelly. If he does not occupy the same level of fandom for you as Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, and Honus Wagner, it is likely due to our lack of multimedia coverage of him.

Kelly became baseball’s first nation-wide household name…the first to transcend the sport. Try to imagine how impactful someone must have been to achieve that level of celebrity without the aid of television or radio. Mike Kelly was the epitome of a star. He was a handsome man who dressed very well, and was very well liked by most everyone. Kelly was personable and a showman – if ever there was a person who was a natural as a celebrity, it was King Kelly. He helped catapult professional baseball into mass adopted popularity.

There are no video clips to see his on-field brilliance, nor can you hear his thick Irish accent in a post-game interview. The truth of the matter is that there is no one on the planet today who can say they saw him swing a bat in our beloved sport in a time when Billy the Kid was an outlaw. All we have are written articles, stories, and yes, baseball cards.

When Kelly got on base, the crowd would go wild, and chant “Slide, Kelly, Slide! Slide, Kelly Slide!” to see his base running genius. He always excited the fans. That’s one of the many reasons why multiple songs, poems, and books have been written about him. Still, without the aid of television or any type of multimedia, the average baseball fan today simply doesn’t know anything about the King of Baseball. Though his popularity was as high as Babe Ruth, his mystique may seem more similar to figures of American folklore like Paul Bunyon, or Johnny Appleseed. It is more common for today’s baseball fan to recall nothing more of him than having heard his name at some point. “King Kelly … isn’t that one of the old guys with a moustache?”

King Kelly’s fingerprints are all over our sport – and even pop culture! It has been said that half of the rules in baseball had to be changed so Kelly couldn’t take advantage of loopholes. He was always looking for an advantage. Here are a few fun facts about him:

- America’s first pop song (Slide, Kelly, Slide) was written about him

- His autobiography was the first of a baseball player

- Some say he invented the hit & run, double steal, catcher backing up first base, and various other plays (some of these were with the help of Cap Anson)

- He claimed to be the first person to use finger signs to the pitcher

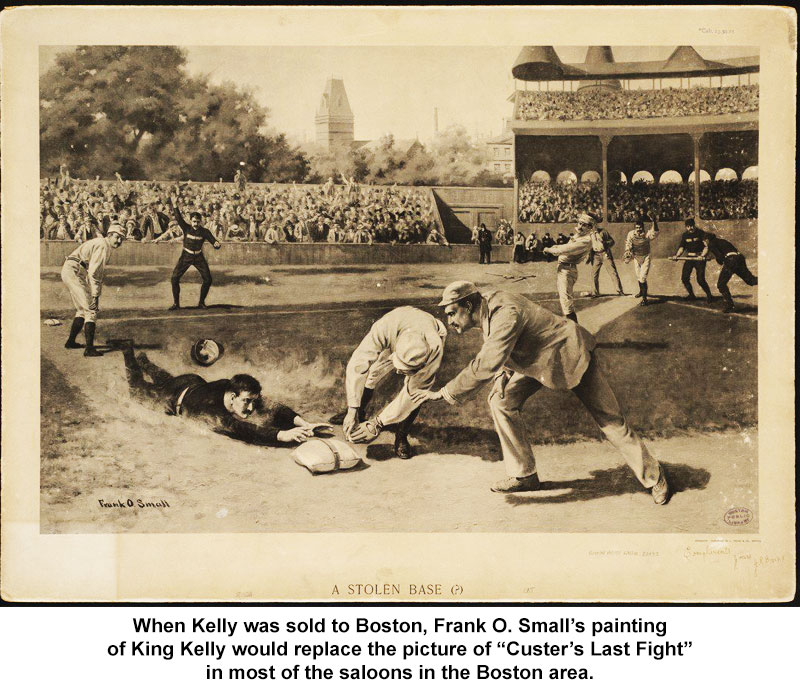

- When he was sold to Boston for $10,000 (a record at the time) Chicago was so upset, many refused to attend the home opener. When Boston was in town, they flooded in to see their favorite player, even though he was wearing an opposing jersey. Chicago fans spent hours in adoration of the newly minted Boston player, even dedicating a song to him. The game was stopped three times to present him with floral arrangements.

- He had many nicknames: King Kelly, the King of Baseball, The Only Mike, The Only, The $10,000 Beauty, and more.

- Speaking of the $10,000 sale, he was so welcomed by Boston, most all saloons replaced “Custer’s Last Fight” with a painting of Kelly sliding into second base.

- The Boston fans were so thrilled to have Kelly, they presented him with a house.

- To get to the ballpark, he would take a ferry to the city where a carriage would await him. Sometimes, fans would even carry the carriage! Oftentimes, Kelly would ride to the ballpark with a monkey on his shoulder.

- Kelly is considered the first subject for autograph seekers. Fans would chase him down with a pencil in hand for him to sign something.

- When Anson took his team to see President Grover Cleveland, Kelly resolved to squeeze his hand so hard as to see if he could make the President wince. He was successful, and according to Marty Appel’s “Slide, Kelly, Slide”, that may have set back championship teams from coming back to visit the White House again until the Nixon Administration.

A King Kelly Story

Here is a fun story regarding King Kelly and arguably the greatest catcher in the 19th century, the NY Giants Buck Ewing from Hugh Fullerton of the Chicago Tribune:

“It happened back in the days when the players of the different clubs were friendly and met at night to discuss and argue over their games instead of sulking separately and discussing their woes.”

He said that day, Kelly had stolen two bases “off the king of catchers,” and Kelly, “kept harping on it until Buck was a bit nettled.”

Ewing told Kelly:

“Well Mike, if Danny Richardson plays second tomorrow, I’ll bet you $50 you don’t steal a base.”

Kelly took the bet, and Fullerton said the following day “three or four of us who knew of the bet sat together in the stands.”

Kelly singled in the third inning:

“(O)n the first ball pitched; he tore for second with a fair start. Buck threw. The ball went like a shot, straight towards the bag, perhaps three feet up the line towards first, a perfect throw to catch any runner—except Kelly. Richardson got the ball five feet ahead of the runner. He was stooped over and swung his body quickly to tag Mike, he expecting the King to make one of his famous twisting slides. Instead, Kelly leaped, jumped clear over Richardson, and lighted flat on his back on top of second base.

“Above the roar of the crowd arose Kelly’s voice, and what he said was this:

“Fifty bucks, Buck.”

There are countless other fun pieces of information about The Only Mike, and if you want to know more, you can pick up one of the several books written about him – the man who was the idol of not only countless fans, but also countless players. Another good link to read more about him is at https://baseballhistorydaily.com/tag/mike-king-kelly

It is likely that in virtually any baseball game you see today, there will be rules enforced and plays made that were either invented, enhanced, or some how affected by King Kelly. Many of his peers, Cap Anson included, called him an absolute genius on the diamond.

A Grail Find

It is for all these reasons and more that I set out to search for some authentic King Kelly baseball cards. But in a world where new cards of every active player are being created almost weekly, I knew my expectations would have to be adjusted. While a quick search on eBay for Mike Trout baseball cards brings around 100,000 results, trying to find a card of King Kelly released during his playing career will typically yield very few results, and oftentimes, the same type of card. There were very few cards made of Kelly during his playing career, and the vast majority rarely show up for sale – especially cards that feature a photograph of him. This isn’t exclusive to Kelly, either – most all 19th century ball players have very little in the way of cards featuring their photograph.

I decided to start my pursuit by going to my favorite vintage website forum – Net54Baseball.com, and put up a want ad for a prominent Gypsy Queen or N173 Old Judge cabinet card.

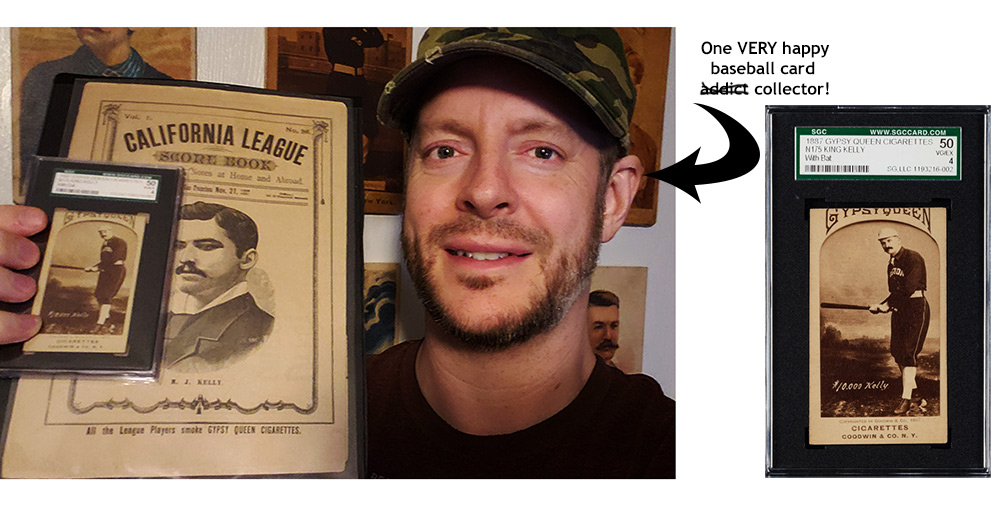

Within days, someone reached out to me. I opened the message, and what I saw made my jaw drop. Offered to me was one of King Kelly’s rarest cards ever – a lifetime grail card by all accounts. The highest graded ever premium sized 1887 Large Gypsy Queen of his. This exact specimen has been used in various articles by baseball’s most famous historians, and posters have been created of it.

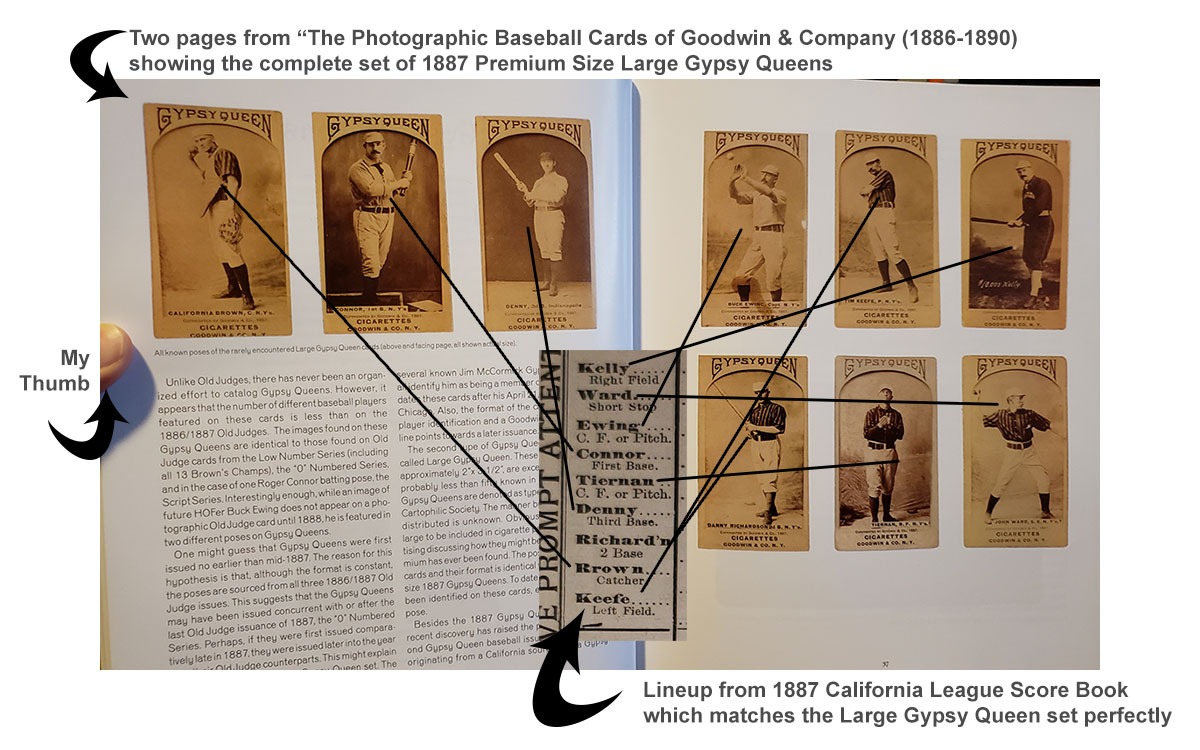

As mentioned previously, Old Judge cards are rare – not a single graded Old Judge card has come close to the quantity of graded T206 Honus Wagner cards, and Gypsy Queens are far rarer. The 1887 premium sized Large Gypsy Queens are on another level. With less than 50 total known of all 9 cards in the set, they are among the rarest of the rare. Why there were only 9 cards in the set – and the subjects selected for the set was a mystery to me, and many others.

It didn’t take long for me to pull the trigger on the highest graded example of one of the rarest cards ever of baseball’s first superstar. This card came along with something else: A good mystery that stretched much further than I had ever imagined.

A Good Mystery

We know that Allen & Ginter, Goodwin, Old Judge and Gypsy Queens were distributed in cigarette packs. Thanks to various advertisements, we know that N173 cabinets and albums could be obtained by sending in certificates.

The mystery is this: How were the premium sized Large Gypsy Queens distributed? They were too big to fit inside of cigarette packages. Where did they come from? There are no known advertisements that discuss how they could have been obtained. Why were they even created? The subjects in the 9 card set seemed odd as well.

To my knowledge, no one knew the answers to any of these questions. No publication, historian, or collector had answers to give. With as highly sought after as Gypsy Queens are, saying it is frustrating that nothing is known about their rarer premium sized counterparts is an understatement. Cards with a known history, and good back story can elevate an otherwise great card to celebrity status – see the T206 Wagner and 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle. They are both incredible cards, but their iconic status is due in part to the mystique that comes from incredibly intriguing back stories.

Since so many years have passed, it is highly unlikely that something will surface regarding the origins of this magnificent 134 year old set, so I guess for my King Kelly, I need to be satisfied with the fact that its origins will remain a mystery.

Or so I thought.

A Museum Find

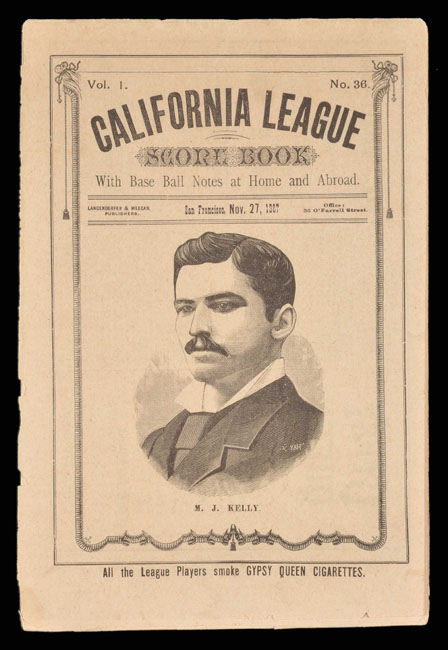

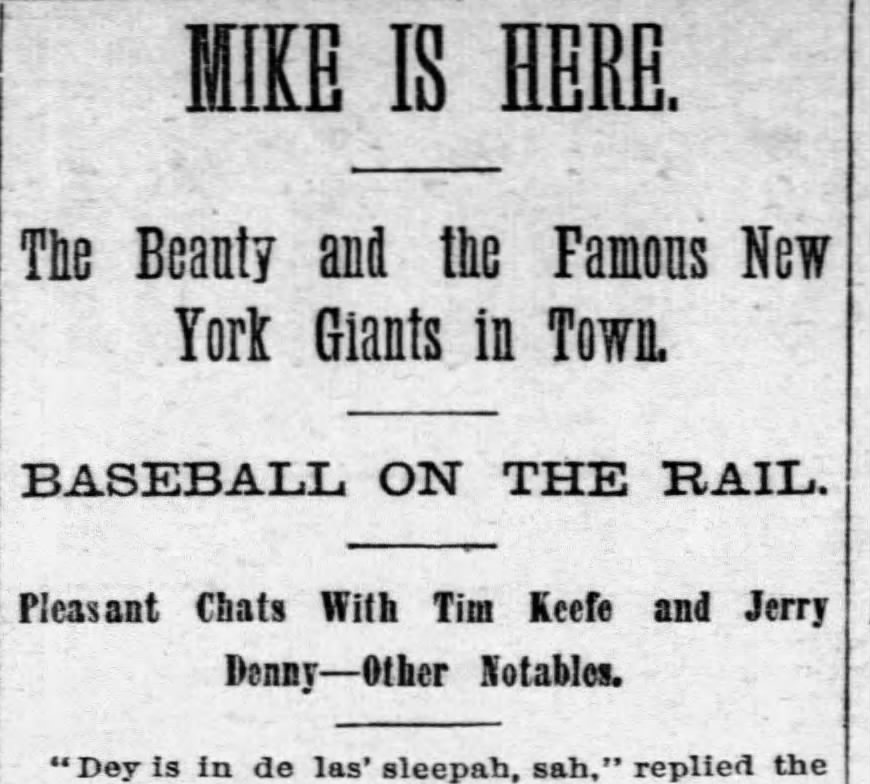

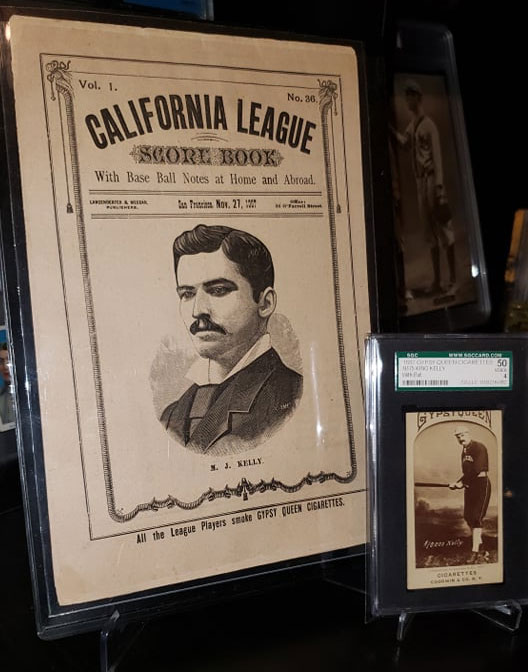

Within days of capturing this monumental card, I put up another want ad. Jay Miller, one of the authors of the “The Photographic Baseball Cards of Goodwin & Company” reached out to me with a fascinating piece of baseball history that neither of us had seen another copy of. A California League Score Book. The front of it looks like a wild west wanted poster, which is expected due to the fact that it fits the time period and region for such ephemera perfectly. The front features a beautiful woodcut illustration of the $10,000 Beauty, King Kelly himself.

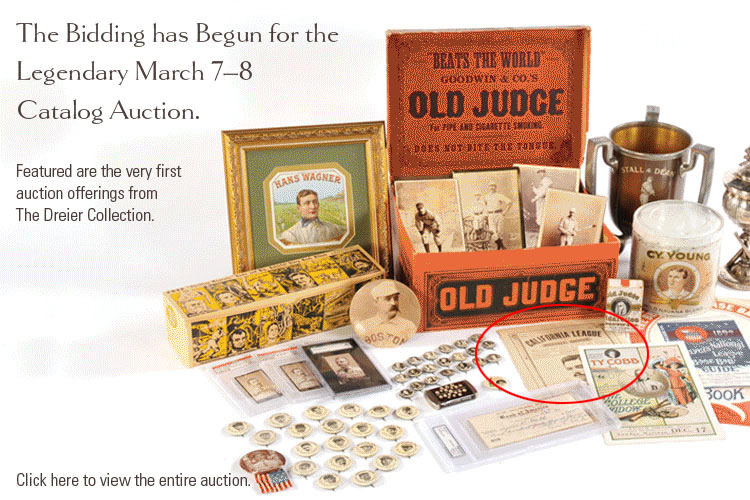

It is a museum worthy piece because it was actually on display in a museum in Santa Barbara. It comes from the Dreier Collection, which was sold at auction nearly a decade ago. Douglas Dreier was kind enough to discuss the piece with me and talked to me about where in the museum it was displayed. Here is a promotional picture I found from the internet archives when it went up for sale nearly a decade ago.

This score book unlocked an incredible piece of baseball history lost to time – so much so that not even the front office of the present day team it represents knew about it up until about 2017, according to one article in the San Francisco Chronicle. To learn more about this, I read up on it in Marty Appel’s “Slide, Kelly, Slide”, discussed further with historian Angus MacFarlane, and researched deeply among the archives of various 19th century newspapers. What I learned was fascinating.

Let’s go back nearly 150 years to learn why this score book was created.

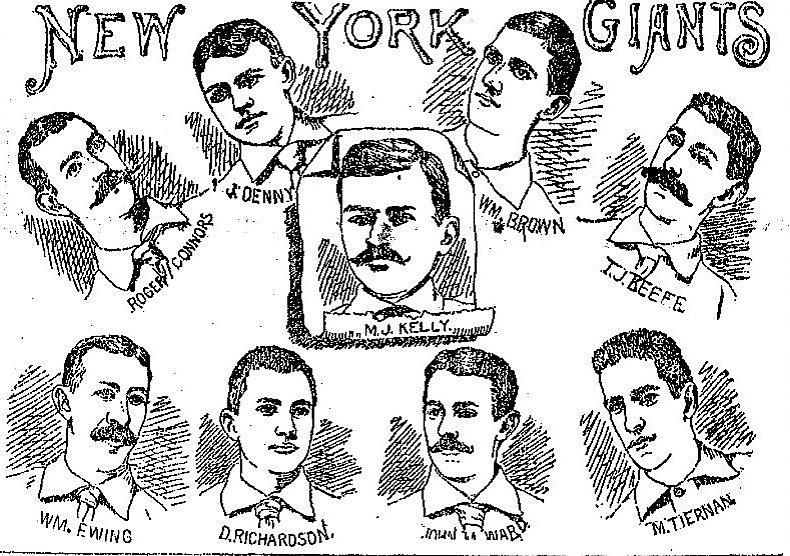

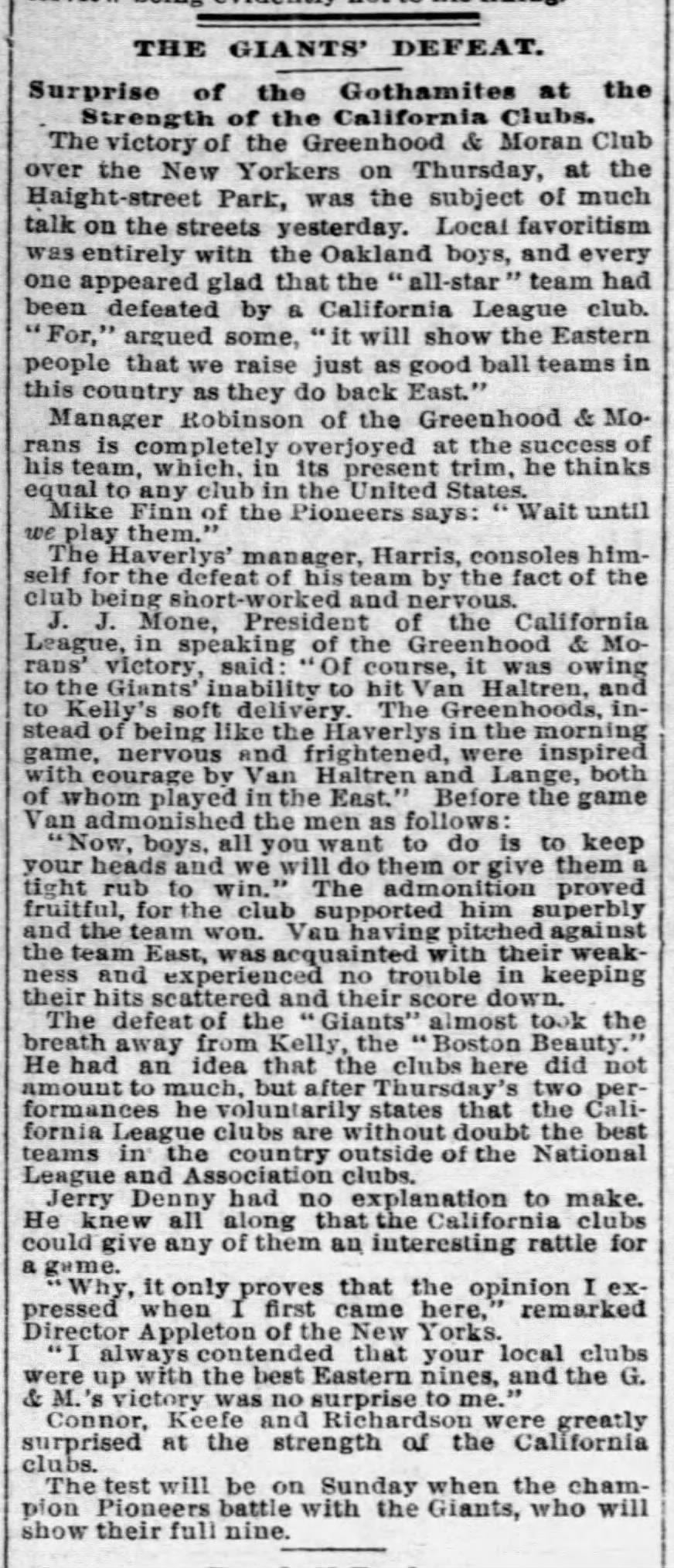

1887 California League Barnstorming Tour

It was a brisk Thanksgiving in 1887 in California. For months, baseball fans were anticipating the arrival of the New York Giants for their barnstorming tour to take on baseball’s best teams from the California league. West coast baseball fans probably debated to no end as to how the games would go. The Giants were originally known as the New York Gothams, but changed their name to the Giants in 1885 allegedly due to their home run hitter Roger Connor’s size – at 6’3″ tall, he towered over most men during this time.

Would NY demolish those from the lesser known teams of the west? Or did the hometown boys have what it took to stand their ground and defend their territory?

The New York Giants were stacked with hall of famers and super stars from top to bottom. Incidentally, they would go on to win the world championship series the next two years in 1888 and 1889.

As if their powerhouse of a team wasn’t enough, they invited star Jerry Denny to be their third baseman for the tour, and to top it off, they brought in baseball’s most popular player, none other than the $10,000 Beauty, King Kelly.

Though the Giants were stacked, the added presence of King Kelly was an incredibly big deal. Songs, poems, and books were written about him. Even the $10,000 check was publicly displayed so fans could see it. Nobody was bigger than baseball’s first superstar, and the entire region waited with bated breath to see this larger than life character who was constantly written about in newspapers, in person.

Baseball players of this time period were extremely superstitious. Perhaps that explains why photographs of the players of the California league were buried under home plate at the start of the series – hoping that maybe it would bring them luck against the Giants of the east.

The season opener on Thanksgiving Day called for the Giants to play two games: One against the Haverlys and one against the G&M’s of Oakland.

It came as no surprise that the Giants handed the Haverlys a loss by winning 9-2. What followed probably did surprise many. The Greenhood and Morans of Oakland dealt a 10-4 loss to the Giants.

This pivotal game caused quite an uproar. Were the California teams fit to play against the best of the best? Or did the Giants keep in mind that they were there for the money, and figured it would be better to put showmanship ahead of winning? Perhaps that’s why they allowed for King Kelly to actually pitch that game.

The next day, the San Francisco Examiner let the Giants have it by gloating about the California victory, and even made mention about how the California League Champions – the Pioneers – couldn’t wait to get their hands on the Giants on November 27th – when the best of the west were set to take on the best of the east. It was must see baseball for everyone. If the G&M’s could man handle the Giants, what would the Pioneers do?

While November 27th was marked on everyone’s calendar, the Giants had one game to get through first. The team from Stockton. Fresh off of a loss and a public berating by the newspaper, the Giants brutalized the Stocktons 26-0. It was a game that the Giants were on a mission to recalibrate everyone’s expectations.

The next day was the game with the champion Pioneers. Everyone was on edge, especially given that the Giants had devastated Stockton the day before. It was for this monumental game that the score book I recently purchased was made, complete with score cards, player biographies, and more.

The front of the score book features a large portrait woodcut of the main attraction: King Kelly, with a line at the bottom stating “All the League Players smoke GYPSY QUEEN CIGARETTES”.

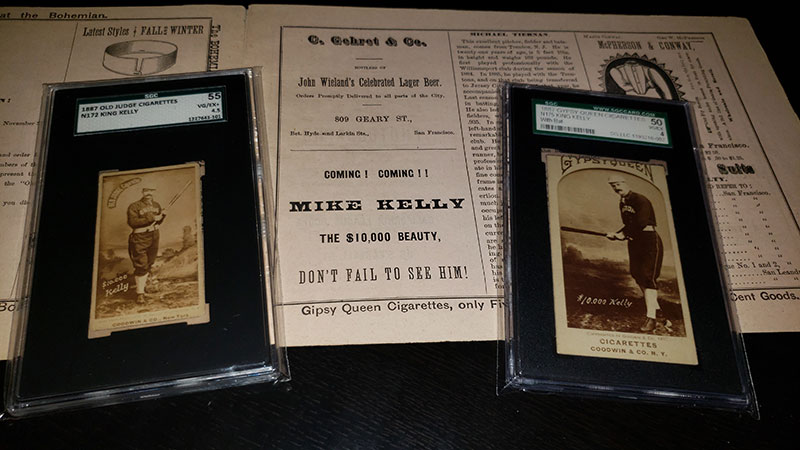

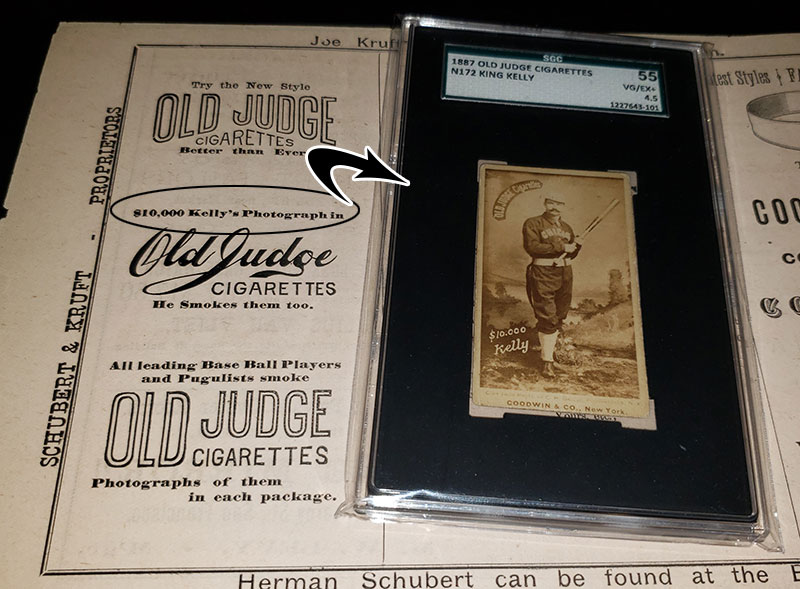

Inside this score book are various advertisements for Old Judge, Gypsy Queen, and Allen & Ginter. The score book also has headlines such as “Coming! Coming!! MIKE KELLY – The $10,000 Beauty. DON’T FAIL TO SEE HIM!” Also mentioned is “$10,000 Kelly’s Photograph in Old Judge Cigarettes – He Smokes Them Too”.

After all of my research on this barnstorming tour, the 1887 California League Score Book meant so much more to me. Little did I know there was much more to discover.

A Connection to American Literature

The San Francisco Examiner coverage of the barnstorming tour predictably afforded a lot of newspaper real estate to writing about King Kelly’s arrival and performance. The coverage may sound familiar, as it reads like a preliminary draft to a famous piece of American literature that stands shoulder to shoulder with the likes of ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas and The Raven.

The name of the piece? Casey at the Bat.

Curiously enough, not only did the author Ernest Thayer write Casey at the Bat; he was also the one who covered the barnstorming tour in the San Francisco Examiner. Though this tour was the last baseball event he covered before moving back east, he sent in the poem to the San Francisco Examiner mere months later on June 3, 1888.

This is what the newspapers said about Kelly’s first appearance in the 1887 barnstorming tour from the SF Examiner …

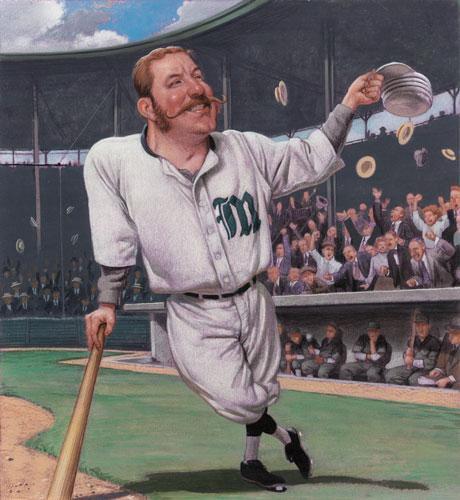

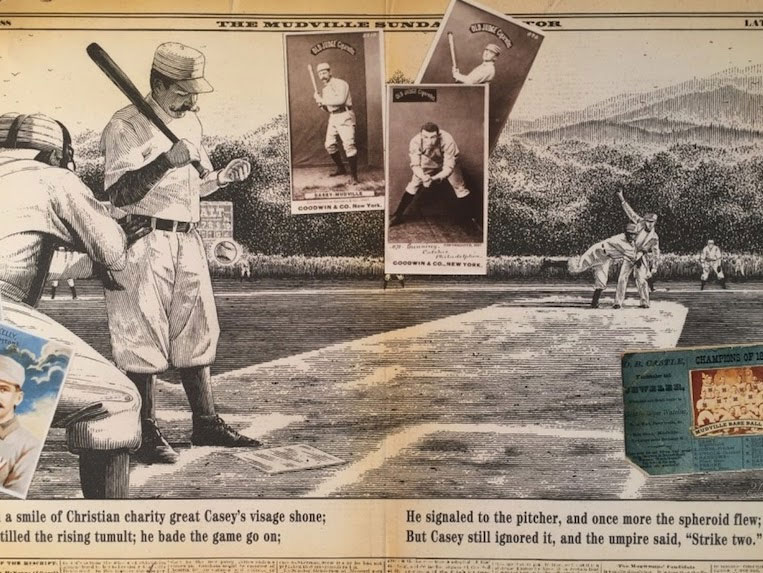

Here’s a modern caricature of Casey from the Mudville Nine.

Readers of Casey at the Bat will find the larger than life showmanship of Casey quite interesting – especially in a crucial part of the game in the poem:

There was ease in Casey’s manner as he stepped into his place;

There was pride in Casey’s bearing and a smile lit Casey’s face.

And when, responding to the cheers, he lightly doffed his hat,

No stranger in the crowd could doubt ’twas Casey at the bat.

Without knowing about King Kelly and his time in the barnstorming tour, the casual reader would assume this is a made up character. No batter would ever face such a crucial time in a real game with this bravado, but perhaps a showman would in an exhibition – a celebrity whose very likeness graced the cover of the score book of such a crucial game. Being hired as the main attraction for an exhibition tour would undoubtedly allow him to ham it up in a game of no real consequence, where he was there because of his showmanship. Kelly, by the way, would go on to perform numerous times on stage, singing, and acting.

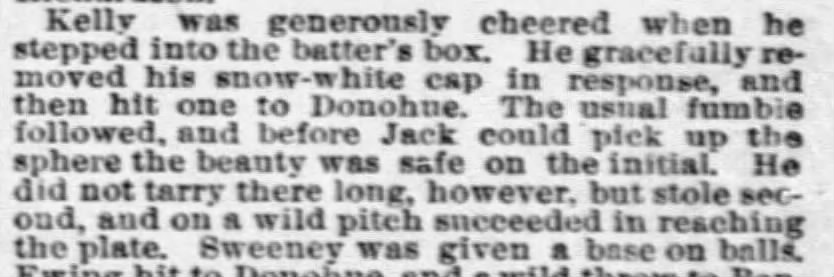

The November 27th game write up curiously spends five paragraphs describing a single King Kelly strikeout in excruciating detail. From the beginning, it talks about how he was greeted with a generous outburst of applause when he assumed his graceful attitude facing the pitcher.

The write up continues by retelling the story of Kelly’s at bat – Keep in mind that four strikes were necessary to strike out…

“One ball,” cried Sheridan, then “One strike, two strikes, three strikes.” The Beauty had not struck at the ball, and he was getting interested.”

The phrase “and he was getting interested” is a curious one, as it suggests that Kelly let the other pitches go by without much so much as a desire to even try – perhaps to build up suspense for the final pitch.

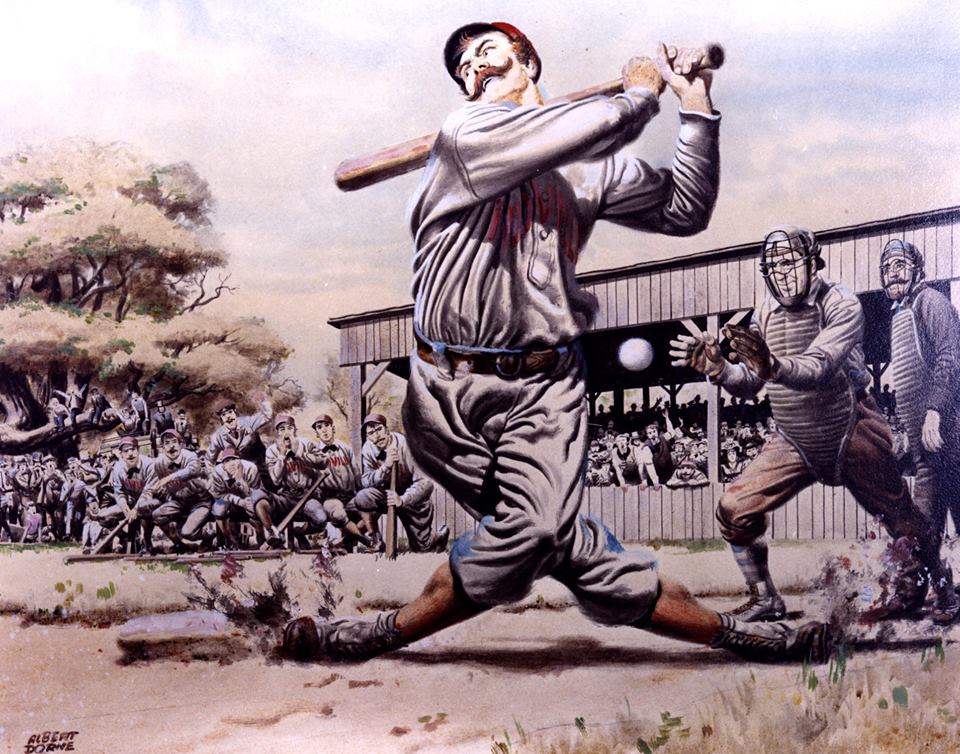

Here is a beautiful illustration by Christopher Bing from his book “Casey at the Bat” – a book well worth purchasing! Here, you can see Casey not interested in the pitch.

The retelling of Kelly’s epic barnstorming tour strikeout continues:

“Lorrigan stood facing Kel for the final effort. In came the sphere, the Beauty made a lunge with his bat which met nothing but air, and amidst the shouts of the crowd the “Only Mike” retired to the bench.”

In spite of the Giants winning the game, the writer of the Kelly’s at bat built up the suspense of the biggest name in baseball being struck out by the hometown hero in dramatic fashion.

But why would Kelly not even get interested until the last pitch? Perhaps that’s why Kelly pitched a game during this series – not to win, but to entertain. His lack of seriousness in desire to win would also explain why he was reported to have joined some “new friends” in the stands for some drinks – during a game! In fact, there were also multiple reports of his drunkeness on the way to California that prohibited the Giants from playing other teams. Early on, there were reports of the the entire tour having been cancelled due to several of the players drinking.

For nearly a century and a half, people have debated as to who the real Casey was modeled after. Given its popularity, a number of baseball players attempted to take credit for being the subject of Casey, but fans during this time saw the similarities between Casey and the biggest name in the game, and assumed they were one and the same.

Author Ernest Thayer was asked a number of times over the years who the real subject was. He was oddly aloof if not misleading, and his responses would vary. Most prominently, he would say it was of nobody in particular, but rather written to memorialize a common theme throughout baseball. This response would prove to be an extremely intelligent tactic, allowing for fan’s dreams to run wild, placing whomever they wanted the hubristic batsman to be in their fantasy. Not being tied to any particular player perhaps helped propel the ballad to immortality. Immersing yourself in the stories that were told of him daily in the newspapers paint a picture that many assumed back then: Casey and Kelly were one and the same.

DeWolf Hopper was a famous performer who could likely credit much of his success to performing Casey at the Bat a reported 10,000+ times. In turn, he can also probably take credit for helping popularize the poem. He was routinely met with praise for his enactment of it, for he didn’t merely recite Casey at the Bat; he performed it. We are lucky to be able to listen to an authentic Hopper performance of the ballad by going to Youtube. Here he is performing it!

Other Inspirations for Casey at the Bat

Thayer reportedly gave two additional differing responses for his Casey inspiration during his life. He once stated nearly half a century later that he modeled Casey not after anyone in baseball, but rather a high school bully with the name of Casey. This response satisfied very few, beyond perhaps borrowing nothing more than the name of Casey.

Another response was reported second hand, stating that Thayer told Hopper it was inspired by his best friend in college, Sam Winslow. Winslow was the captain of the baseball team while the two attended Harvard, and Thayer did take in a number of college baseball games. Still, things don’t quite seem to line up – at least for Winslow to be the model for Casey. Rich Davis of CaseyAtThe.Blog wrote an article named “The Ballad of Sam Winslow” where he details his findings based upon research and even interviewing the living relatives of Sam Winslow.

Upon investigating, we find that Winslow was not best known for his hitting prowess, but rather as a star pitcher. One former newspaper editor notes that as a pitcher, Winslow loaded up the bases in the 9th inning three times, only to get the final batter out. These adrenaline packed games would surely leave a lasting impression on fans such as Thayer, which in turn, could have influenced the adrenaline found in Casey at the Bat. As Davis concludes, it is possible that Thayer may not have immortalized his best friend as the prideful batter striking out in embarrassing fashion, but rather as the hero for which the spotlight never fell upon during the ballad: The pitcher – a technique that would have been consistent with both Thayer’s brand of humor and the literary training that he received at Harvard. This take is something that Winslow’s family members seem to think is plausible as well.

Evidence for Kelly and the Barnstorming Tour of 1887

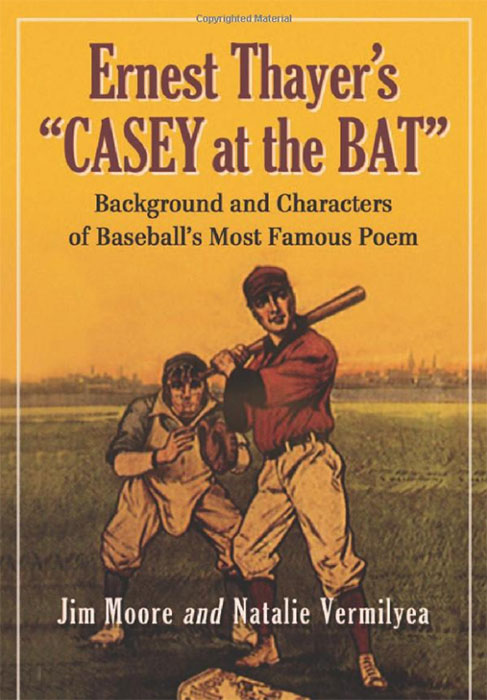

Thayer’s biographers seemed to take the connection between Casey and Kelly quite seriously in their book “Ernest Thayer’s “Casey at the Bat”: Background and Characters of Baseball’s Most Famous Poem” (Jefferson NC.: McFarland & Co., 2012)

A month or so after Casey at the Bat was published, a “parody” named “Kelly at the Bat’ was published, which traded Casey’s name out for Kelly. This version of the poem was published in various newspapers across the United States, and was loved by many. The biographers in the aforementioned book suggest that had this not taken place, Casey at the Bat would have suffered the same fate as countless other newspaper ballads. For a time, many thought that Kelly at the Bat was the original, and Casey at the Bat was the parody.

The song written about King Kelly the following year “Slide, Kelly, Slide” also makes mention of Casey. You can be sure that these connections fans made between Kelly and Casey were just the tip of the iceberg. While none of this is absolute proof that Kelly and Casey are one and the same, it does provide us with perhaps what the general consensus was amongst the masses in the 19th century during the time of its release.

Thayer seemed to be overtly annoyed at people assuming Casey was modeled after Kelly, and appeared to distance himself from such a connection. This would make sense if Kelly’s hubris rubbed him the wrong way, and he wanted the poem to be more universal. It probably didn’t help much that Kelly performed the poem in front of people multiple times, embracing the folly of his supposed Casey caricature. Certainly Thayer didn’t appreciate the parody of Kelly at the Bat being seen as the genuine article, either.

Still, there is good reason why so many assumed Kelly and Casey to be one and the same. The bravado of Casey seems to perfectly match Kelly to a tee, particularly during the 1887 California League Barnstorming Tour, and Casey’s failure may have been an outlet for Thayer who perhaps didn’t appreciate Kelly’s antics. Kelly was quite the showman – a trait that helped propel him to celebrity status far among anyone else who picked up a baseball bat during this era, but was undoubtedly polarizing. Surely his drinking habits prohibited him from being at his best on the tour, which could make for good fodder for being the failed batsman in the poem.

The poem details an often overlooked and very unusual tidbit: After Casey fails to swing at the first pitch, and the umpire calls it a strike, the crowd calls for the umpire to be killed. When this happens, Casey saves him, by calling off the dogs. Interestingly enough, in a game where Boston lost to New York thanks to a few bad calls earlier that year, the crowd went after Umpire Jerry Sullivan, who was ultimately protected and saved by none other than King Kelly.

From the benches, black with people, there went up a muffled roar,

Like the beating of the storm-waves on a stern and distant shore;

“Kill him! Kill the umpire!” shouted someone on the stand;

And it’s likely they’d have killed him had not Casey raised his hand.

To make things even more interesting, the poem seems to not only draw heavy inspiration from King Kelly, but other specifics from Thayer’s time covering the barnstorming tour of 1887 with the Giants as well. The characters mentioned in the poem Cooney, Blake, and Flynn all played in the barnstorming winter tour of 1887 and all played at one point or another for Stockton – the team that the Giants pounded 26-0.

Speaking of Stockton, it was also known by another name once upon a time: Mudville! The name of the town mentioned in the poem. Even the topography described in Casey at the Bat matches the setting of the California Tour.

The end of the winter barnstorming tour was closely followed by the end of Thayer’s journalistic career. He left the profession just as he had loaded up with all the fodder he needed to write his baseball ballad mere months later.

Many historians and authors of books on the subject agree, there is a ton of compelling evidence that Casey at the Bat was inspired by King Kelly and his time in the California Tour, perhaps even pinpointing it down to the very at bat on November 27, as noted in the SF Examiner. As with most literary pieces though, Casey at the Bat is likely an amalgam of Thayer’s life experiences, with King Kelly in the 1887 barnstorming tour being arguably the foundation for which it was written.

Unlocking the Gypsy Queen Mystery

All of this leaves us with one last mystery: The Large Gypsy Queen card of King Kelly. Why are there only 9 cards in the set? Upon becoming a student of the 1887 barnstorming tour, all became crystal clear. The 9 players featured in the Gypsy Queen set each represented a position…like a specialty all-star team. 7 are Giants, 1 is an Indianapolis player, and of course, King Kelly. This got me to thinking … what if these players matched the lineup in the 1887 California League Score Book?

I checked, and name by name, they matched perfectly! This set appears to have been created specifically for the tour itself. Gypsy Queen was quickly becoming the most popular cigarette in the area, so it would make sense for Goodwin & Co. (the makers of Gypsy Queen) to spend their marketing dollars around such a monumental barnstorming tour by advertising in the score book, and even creating a set specifically for the tour.

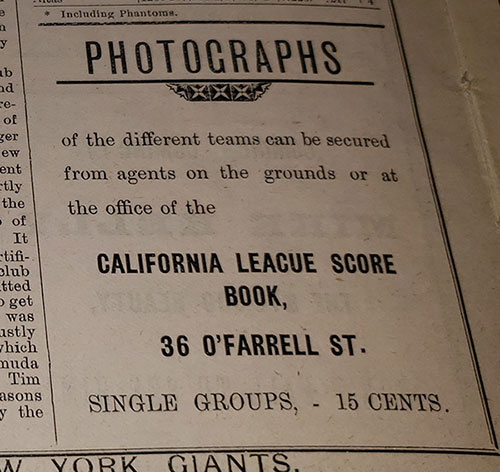

The score book itself even makes mention of how photographs of the different teams were available, as well as single groups. Could this pertain to the large Gypsy Queens?

I reached out to some historians and prominent 19th century baseball card collectors about my discovery – all of this turned out to be news to them as well and they mentioned this was an incredible discovery. A regionally based offering of a score book and set of baseball cards would certainly explain their scarcity, but why are only less than 50 subjects of the set in total known to exist? Why hasn’t another score book surfaced? To add more historical context, we must dig even deeper.

The San Francisco Earth Quake of 1906

“San Francisco is gone. Nothing remains of it but memories and a fringe of dwelling houses on the outskirts.” – Jack London

Nearly 20 years after the tour, on April 18th at 5:12 AM, the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906 rocked the region measuring 7.9 on the Richter scale. Fires raged for several days as it devastated the area, burning up more than 80% of the entire city. There is a good chance the vast majority of all relics of the barnstorming tour of 1887 were burned up over 100 years ago.

Casey at the Bat Rookie Card?

When I first purchased the 1887 Large Gypsy Queen King Kelly, all I knew was that I was excited for the once in a lifetime find for one of my favorite players. Little did I know that I was about to embark upon the baseball card version of the Da Vinci Code and Indiana Jones all wrapped up into one. Since it appears to be clear that it was created for a special set commemorating the 1887 California League barnstorming tour which could have been a key influencer for Casey at the Bat, one may consider the premium sized Gypsy Queen Kelly to also be Casey at the Bat’s rookie. A relic not only of historical baseball significance, but also of historical American literature significance.

While I’m ecstatic to be the owner of what could quite possibly be considered Casey at the Bat’s rookie card, I found myself more deeply in love with baseball in a time when television and radio didn’t reach. As I was reading box scores and summaries of each game, I found myself audibly chuckling at Kelly’s exploits – believe me, there were many of them. I got lost in the colorful commentaries, yearning to know what would happen in the next game. It all became clear to me how Americans in the 1880s were fanatical about the game that I grew up being fanatical about in the 1980s, even though they had nothing more than newspapers and baseball cards to fuel their imaginations.

Seven years after the 1887 California Tour and the Large Gypsy Queen set was produced, baseball’s first superstar King Kelly passed away at the age of 36. Baseball mourned its most captivating character, and America lost one of its first celebrities. The death of the $10,000 Beauty left what seemed to be some impossibly big shoes to be filled in the game of baseball. Those shoes would be eventually filled by someone who was born 90 days after Kelly’s death. His name was George, but we know him best by his nickname the Babe.

I am extremely grateful to be the caretaker of these fine pieces for the time being. If there is one thing that history has taught us, it is that they are survivors and will likely live on far longer than I will. I only hope to do an adequate job in telling their entertaining story.

At my core, I still feel like a kid who gets excited about a pack of 1989 Donruss. But then again, that’s probably exactly the same feeling kids got well over a century ago when they were chasing the $10,000 beauty, King Kelly.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.